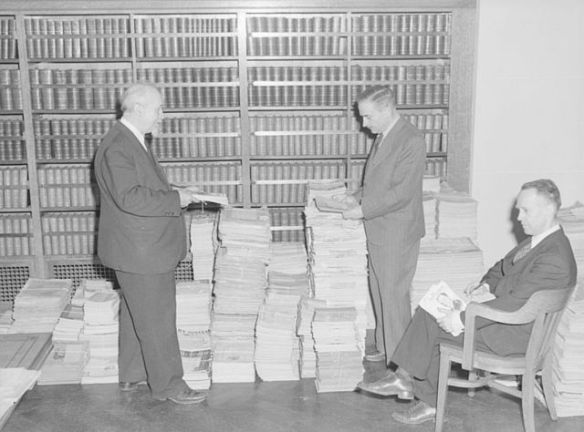

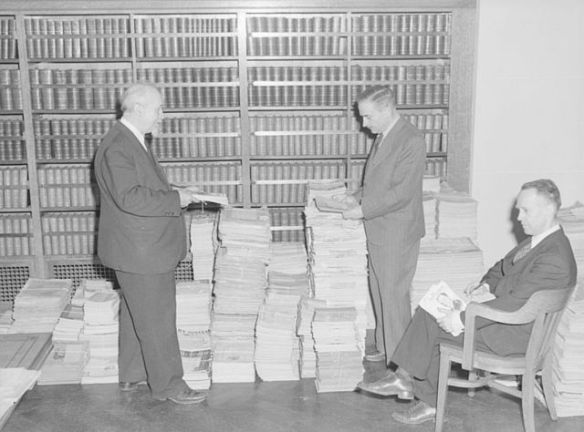

Saint-Sulpice Library (now Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec), Saint-Denis Street in Montreal. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

I’ve mentioned the paper trail before. It’s something that fascinates me but something I try to avoid when I’m writing. See How to Get Distracted Writing Historical Fiction. Today I am recovering from a small operation and I am not in the mindset to work on my fiction so I do what I normally do when I can’t write for various reasons. I read.

Less than a year ago I discovered crime fiction. Not the crime fiction that most people read but the crime fiction written by women in the 1950s and 1960s. For an historical novelist it is a wonderful world to discover, particularly for someone like me that has hardly ever read mysteries. The storylines are simpler than today’s books (burdened as they are with CSI, multiple plotlines, advanced technology etc). Instead these novels are peopled with interesting heroines and filled with everyday details that have now become historical fact. Think 10 cent jewellery stores and the road to Geneva early evening with not another car to be seen.

I began with Holly Roth (who is still my favourite) and devoured Shadow of a Lady, The Content Assignment, The Mask of Glass and The Sleeper. I was recently in Tasmania visiting the Salamanca Markets and was lucky enough to find a book by Helen McCloy, He Never Came Back, published in 1954 for only $2, (a 1961 green Penguin). I began reading the book and was not distracted until I got to this line on page 51. (A friend of the main character, Sara Dacre, has disappeared and she is worried. She is discussing what has happened with her aunt Caroline and an elderly man).

“It’s like bridge,” said Caroline. “You have to keep everything in your mind at once – past, present, and future. Book murders are more amusing than murders in real life, but, when it comes to disappearances, I don’t think any books have touched the real cases. Lord Bathurst, Marie Celeste, Charlie Ross, Dorothy Arnold. And Judge Crater.”

I knew of Marie Celeste of course and being female was immediately more interested in the disappearance of a woman than a man, so I honed in on Dorothy Arnold in google and came up with this entry in wikipedia. And so the paper trail unwinds and the book is left open at page 51.

It seems Dorothy Harriet Camille Arnold “was an American socialite who disappeared while walking on Fifth Avenue in New York City in December 1910. The circumstances surrounding her disappearance have never been resolved and her fate remains unknown.”

I read the entry and discovered a link to List of people who disappeared mysteriously and of course clicked on it. How many people can resist a link like that, I ask you? Definitely not me. As I’m researching and writing a trilogy set in Paris and Sydney in the 1920s, I clicked on the link to the 1920s and scanned through the names. Among them was Glenn and Bessie Hyde. I already knew about them from a novel I read a number of years ago. And as I type these words I’m off on another paper trail (web search) to find the title of the book. Voila! Grand Ambition by Lisa Michaels. It is an enthralling book and I highly recommend it.

I checked the other names and read about The Lost Battalion. Having recently completed a final edit of a novel set during WWI this was of particular interest. In 1921 Charles Whittlesey 37, “American soldier and Medal of Honor recipient who led the Lost Battalion in World War was last seen on the evening of 26 November 1921, on a passenger ship bound from New York City to Havana, and is presumed to have committed suicide by jumping overboard.”

On reading about the Lost Battalion I discovered that a pigeon named Cher Ami was responsible for saving the lives of 194 men by delivering a message whilst badly wounded, 25 miles to the rear of the action in just 25 minutes. How good is that?

Although the 1920s list is fascinating (and I will probably go back to it later) my eyes were drawn to the 1930s and the name Barbara Newhall Follett. She “was an American child prodigy novelist. Her first novel, The House Without Windows, was published in 1927 when she was thirteen years old. Her next novel, The Voyage of the Norman D., received critical acclaim when she was fourteen. In 1939, aged 25, she became depressed with her marriage and walked out of her apartment with just thirty dollars. She was never seen again.”

Of course you can probably guess what I did next. I read all about the child prodigy and decided I wanted to read her novel The House Without Windows. You can download it here. And so in the nature of paper trails (web searches) which often seem to be very Alice in Wonderland or Oscar Wildeish, we began with a 1950s crime novel and followed the trail to an American socialite, a long list of missing persons, took a detour rafting down the Grand Canyon, found a Lost Battalion, a Medal of Honour winner, an amazing pigeon, a child prodigy and ended up with what? A book of course! And I’m off to read the Helen McCloy after being rudely interrupted by a paper trail four hours ago.